How Fiction Rewires Your Empathy - One Story at a Time

Perspective-taking, emotional transportation, and your brain on stories

Imagine you’re handed a book. You flip the cover, settle into your favourite chair, your cat sits on you in a highly inconvenient position, and you begin to read. For the next few hours, you live someone else’s life. You wander unfamiliar streets, feel fears that aren’t your own, celebrate victories you didn’t earn. When the final page turns, you close the book and return to your world, changed. That is the power of fiction.

As Homo narrans (ht to

), we have been telling ourselves stories of gods and monsters, royals and rebels, heroes and villains forever. But only recently have psychologists and neuroscientists begun to quantify fiction’s power over our minds. It turns out that reading fiction is more than just a good way to fill your bookshelf for Instagram. It’s a rehearsal stage for the moral and emotional challenges of our lives.In 2006, psychologist Keith Oatley and colleagues measured people’s exposure to fiction by testing recognition of contemporary novelists (Bookworms versus nerds). They discovered that those who knew the works of the likes of Jane Austen or Toni Morrison scored higher on empathy and social-perception tests than those who preferred non-fiction or were non-readers (the horror!). These differences were still there even after controlling for personality traits. That suggests the act of reading itself, not just being someone who likes reading, is fuelling the test scores.

This finding led to other experiments. One study by Kidd and Castano (2013) randomly assigned participants to read a short piece of literary fiction, a best-selling genre (think sci-fi, romance, or thriller) story, or a dry report of the same events. Only the literary group improved on “theory of mind” assessments - tests that measure the ability to guess the beliefs and emotions of others. So, immersing yourself in a story rich with psychological nuance produces an empathy boost.

Another experiment compared people who read a fictional story about prejudice against Muslims with those who read a fact-based news article about the same topic. The fiction readers showed more positive attitudes toward Muslims afterwards, suggesting that emotional identification through story has a stronger effect than just the facts. Stories give us a chance to experience the lives of others in quick time.

Perspective-Taking

Fiction invites you to inhabit minds unlike your own. You sit beside Elizabeth Bennet in the drawing room, understanding her frustration with the inscrutable newcomer to the social circle at Meryton. You hitchhike through the galaxy beside Arthur Dent, towel in hand, feeling his bewilderment at intergalactic bureaucracy. In doing so, you practise perspective-taking. Every time you speculate about a character’s motives, you strengthen the neural pathways that help you read body language at a party or sense discomfort in a colleague’s email.

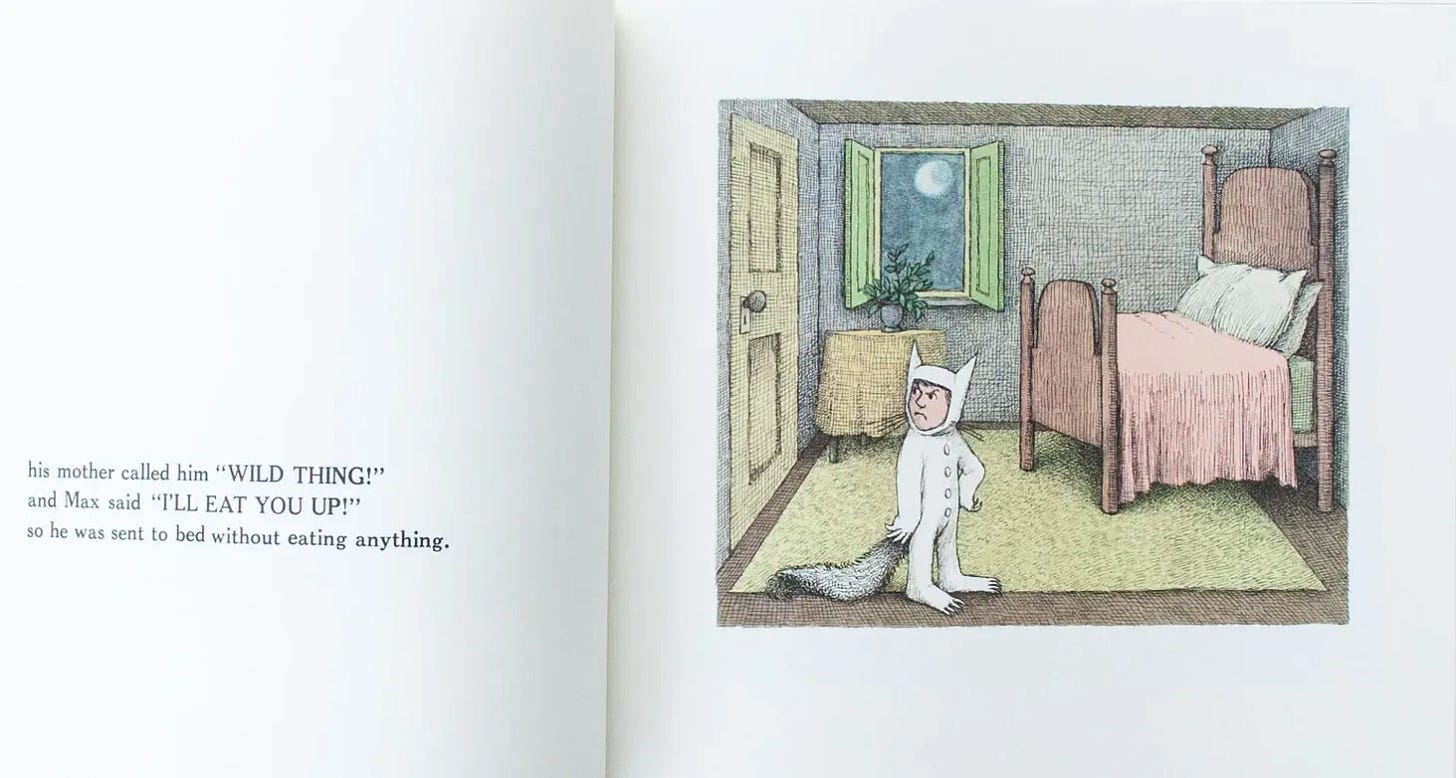

We sort of expect children’s literature to foster these skills, but overlook the effect on our adult selves. Picture books and novels more directly ask young readers to consider how characters feel and why they act the way they do. These moments are often scaffolded by teachers or parents. “How do you think Max felt when he was sent to bed without dinner?” This helps establish the habit of thinking beyond one’s own experience. It’s no surprise that early exposure to stories correlates with empathy later in life. So, it shouldn’t be hard to believe the same thing continues into adulthood.

Emotional Transportation

Empathy is more than an intellectual exercise. It’s a felt experience. When Madame Rosa hides her fear of death behind sarcasm and stubborn dignity, you don’t just understand her. You ache with her. When Frodo’s burden grows too heavy, you feel a knot of anxiety settle into your gut. This “emotional transportation” is fiction’s magic. As you absorb a story, your brain releases chemicals (your favourite types: oxytocin and dopamine) that spark social bonding in real life. It’s a safe simulation of compassion. You can confront another person’s (or hobbit’s) pain from the comfort of your living room.

People who feel emotionally immersed in a story are more likely to help others in real life. One study found that participants who read about a character in distress were more likely to offer help to an unrelated person afterwards, especially if they had identified emotionally with the character’s plight. It’s as if fiction doesn’t just train us to feel, it trains us to act. And as we know, action is where heroism lives.

Fiction Is Practice for Moral Action

These cognitive and emotional workouts add up. Bookworms amass small empathy gains that snowball into real-world skills. Over months and years, they become better listeners, more tolerant neighbours, more likely allies in a crisis. When the moment comes to call out a bully in the corridor or step in to help at a car accident their heroic reflexes have long been humming quietly, ready to fire.

This mirrors how we train for other things. No one becomes physically fit from one gym session. I’ve tried. Many times. Likewise, no one becomes morally courageous from one brilliantly crafted story. But repeated exposure to other minds, other lives, other truths… well, that builds the readiness to act when it counts.

So the next time you’re reading, think of it as stepping on stage in a virtual theatre for empathy. If you take that stage seriously you’re preparing to be a better person. A more empathic person.

And if the time for heroism comes, that preparation may be the thing that tips you towards action. Not because you’ve memorised some rules and definitions, but because you’ve practised caring over and over again.

One story at a time.

~ Matt

This is part 1 of .. maybe 5? .. pieces on empathy through storytelling. Buckle your seatbelt.

I loved this piece. Thank you! :)

Seatbelt buckled